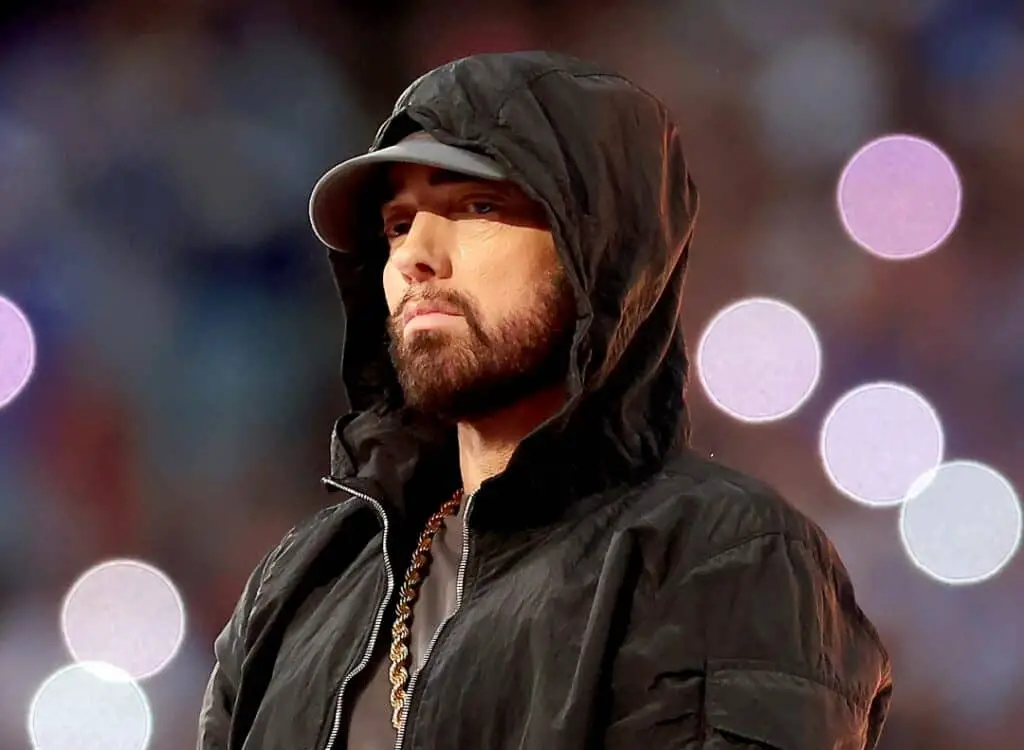

Eminem tells his rap story to New York Times.

The hip-Hop genre celebrates its 50-year anniversary in 2023, and New York Times connected with 50 rap artists who represent different generations, regions and styles and asked them to share their personal stories, focusing on musical upbringing, influences and career arcs.

One of the 50 rap artists is none other than Eminem, who rarely gives interviews but decided to reflect on his legendary career.

Eminem: “My Uncle Ronnie had the “Breakin’” soundtrack. I was, like, 11 years old, and he played me Ice-T’s “Reckless” before I’d seen the movie. Uncle Ronnie used to breakdance and he taught me a little bit, showing me some moves. From that moment I knew there was nothing else — no other kind of music that I would ever like again — aside from rap.

We used to bounce back and forth from Missouri, and shortly after that we moved to Detroit, and we were staying at my Grandma Nan’s house. I had a tape player, and I found WJLB. There was this D.J. named the Wizard. He would play from, like, 10 to 11. I would just hit record on my tape and I’d go to sleep and get up for school to see what I got: “Go See the Doctor,” KOOL MOE DEE, UTFO. I just wanted everything — give me everything that rap has: RUN-DMC, Fat Boys, LL.

Every time LL dropped something it was, like, he was the best, no one’s touching him. LL Cool J was everything to everybody. You know, I always wanted a Kangol.

My first rap, I was 12-ish, when LL Cool J, “Bad,” came out. I would be, like, just walking around my Aunt Edna’s house, thinking of rhymes and writing thoughts down. It was a complete LL bite, but it was something that I dabbled in. I would be sitting in school sometimes and a line would hit me.

And then Run-DMC would drop a new album and you’d be, like, “This is the craziest [expletive] I’ve ever heard.” “Yo, this is as good as rap can get, lyrically.” And then Rakim changed the way people thought about rap.

It just kept advancing to the next level. I was there to watch its conception and its growth. Everybody was trying to one-up each other. It went from rhyming one- or two-syllable words to rhyming four and five and six. Then Kool G Rap came along and he would rhyme seven, eight, nine, 10.

But I was a sponge. I would gravitate towards the compound-syllable rhyming, like the Juice Crew. Lord Finesse, to Kool G Rap, to Big Daddy Kane, to Masta Ace, Redman, Special Ed. I don’t even think I understood why I liked it. I had a couple of friends that had to point out to me how many syllables somebody was rhyming.

And then Treach from Naughty by Nature came along and he was doing all that, too. He was cool, too — his image and everything. I wanted to be him. When the first Naughty by Nature album dropped, that whole summer, I couldn’t write a rap. “I’ll never be that good; I should just quit.” I was so depressed, but that’s all I played for that summer. Proof thought Treach was the best rapper, too. Every time he would drop an album I would just be, like, Son of a bi–h.

Nas, too. I remember The Source gave “Illmatic” five mics. I already knew I liked Nas from “Live at the Barbeque” with Main Source, because his verse on that is one of the most classic verses in hip-hop of all time. But I was, like, “Five mics, though? Let me see what this is.”

And when I put it on, “And be prosperous/though we live dangerous/Cops could just arrest me/Blamin’ us/We’re held like hostages.” He was going in and outside of the rhyme scheme, internal rhymes. That album had me in a slump, too. I know the album front to back.

There was three or four years, maybe, where I kind of dipped out of listening to rap. I was so on the grind in the underground. I didn’t have money to buy any tapes. Every dollar, every dime that I had went to either studio time or to buy Hailie diapers.

Tuesday night I would go to the Ebony Showcase on Seven Mile. Wednesday night would be Alvin’s. Friday night would be Saint Andrew’s. And then Saturday would be the Hip Hop Shop.

Proof was hosting open mics at the Hip Hop Shop, and they started having battles. The first one that I got in — it was actually the first battle there — I won. And then the second battle, I won it again. I realized maybe I should try to go out of state. So I would hop in the car with friends and drive down to Cincinnati for the Scribble Jam.

Back then, you had to go off the top of the head. If you didn’t you’d get booed offstage. So I learned from watching Proof that you can freestyle, but just have a couple lines in the back of your head, a couple of punchlines you know you want to use, and then freestyle around that.

Coming up in the battle scene was the greatest thing to happen to me because I knew what lines were going to get a reaction from the crowd. That’s what I would focus on. So when I got signed with Dre, I was trying to translate that to record, to get that reaction. I would picture the listener sitting there and what lines they might react to. I just used that as a formula. Like, “How you gonna br–stfeed, Mom?/You ain’t got no ti-s.”

When the first Onyx album dropped, Sticky Fingaz was so great at saying that kind of [expletive]: “I’m thinking about taking my own life/I might as well, except they might not sell weed in hell.” And Bizarre was really great at that. If we reacted to it, then we thought other people would, too. That shaped my whole career, you know?”

Check out all other stories from rappers like Bun B, Styles P, LL Cool J, Lil Baby, 50 Cent, Cardi B, RZA, Busta Rhymes, Ice Spice, Lil Wayne, Ice Cube and more.

50 rappers who capture the sweep of hip-hop — across generations, sounds, cities and styles — tell the story of a genre that went from a new art form to a culture-defining superpower, in their own words. https://t.co/DCWkgHqAGo

— The New York Times (@nytimes) July 19, 2023